Marriage

Muriel (née Fraser) became Ralph Hodgson’s second wife. Information about her is scant and most of what we know comes from comments made by Silvia or from Harding’s biography about Hodgson. *

In February 1920 Dolly, Hodgson’s wife of 24 years, died after several years of illness. This coincided with a period when Hodgson had no permanent job or home. He spent the next few months drifting around friends and relatives who did their best to provide him with food and consolation. There is some suggestion that he might like to have married Silvia and, evidently, they went on a short holiday to the Isle of Wight later that year. Silvia was clearly enamoured of him and influenced by his opinions but marriage wasn’t to be.

In November 1920, Hodgson met Muriel (who was in her mid-30s) at a dinner party given by the poet Harold Monro (1879-1932) and his wife Alida. He was bowled over and, not long after, they met for lunch. Muriel was born in Montreal and, in December, she went back to visit her family. She didn’t return to London until the following May but, whilst away, Hodgson wrote constant, amorous letters. By June 1921, they were married at Holy Trinity Church, Brompton.

Along with Uncle Charles, who knew Hodgson through work, Silvia grudgingly attended the wedding. In her 1962 essay, she describes Muriel as having ‘black hair, grey eyes, a beautiful slim figure and the loveliest feet imaginable’ – this last being an unusual observation! She was well read but ‘quick-tempered and not afraid to stick to her own opinion’. As Hodgson also held strong opinions, it perhaps didn’t bode too well for their relationship. Silvia also wrote that she ‘didn’t want to marry him myself but it was annoying to see him married to someone else’. After a few initial ups and downs, however, Muriel and Silvia (who were similar in age) became good friends.

*Dreaming of Babylon: The Life and Times of Ralph Hodgson by John Harding (2008): Greenwich Exchange, London

1924-1926

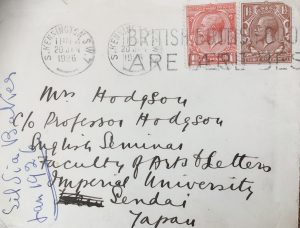

Neither of the Hodgsons had a job at this time and money was in short supply. Unexpectedly, but conveniently in financial terms, Hodgson was offered a post as a visiting Professor at Sendai University, Japan. His appointment was to run seminars on English Literature & Poetry in the Faculty of Arts & Letters. To the surprise of their respective families and friends, in the Autumn of 1924, they set off on the long journey to the Far East.

Muriel was an independent thinker and fighter which appealed to Hodgson but he was very controlling. She had no special friends in Japan and felt hemmed in. The demands of living in such an alien culture and language must have exacerbated the situation. Things were not going well and fearsome marital rows developed. Meanwhile, her mother was nearing the end of her life and, in April 1926, Muriel left Sendai for Canada. Sadly, by the time she arrived, her mother had already died.

Rather than return to Sendai, she took up a job in a bookshop. Hodgson eventually sent her condolences and some money, hoping for a reconciliation – but on his terms, which she could not accept.

1927-1933

In August 1927, he returned to England for a few months, accompanied by a young American missionary teacher, half his age, called Aurelia who was on her way to take up some studies in the States. Muriel also returned to London and stayed with the Rothensteins. She needed to find out where she stood with Hodgson and threatened to take him to court if he didn’t provide her with some financial support. Harding implies that she didn’t learn about Aurelia for another few years.

Muriel then became ill and Hodgson went to see her but declared that ‘though they might remain friends, they would never live together again’. In due course, Muriel needed an operation and Hodgson visited her on a daily basis. However, following an argument, all communication came to an abrupt end. They eventually divorced in 1933. A few months later, in October, Hodgson married Aurelia (Bolliger) in Japan.

Postscript

After their separation, Muriel was offered the post of Lady Superintendent at the Royal College of Art by William Rothenstein. Silvia wrote in 1962 that ‘there were 400 students at the College and many of them still remember Muriel with affection and admiration’.

According to Harding, in the 1950’s, Silvia sent a letter to Hodgson suggesting that he might write to Muriel, as she was going blind – but he declined to do so. She died in London in 1961.

CORRESPONDENCE (to Muriel)

There are no letters from Muriel but, significantly, we have several letters which Silvia wrote to Muriel. With most other correspondents, it is the other way round – copies of their letters are available but Silvia’s replies, if they exist, have not yet been sourced.

Since the original list of letters was uploaded, some more letters have surfaced (marked *). The list has, therefore, been re-configured, as below.

(January 2022)

1924 August 21st – Dieppe, France *

1924 September 21st – Harrington Road, SW7 *

1925 March 2nd – London Zoo Restaurant *

1925 April 7th – Mentone, France + April 12th (Easter Sunday)

1925 June 15th – Alfred Place, SW7

1925 August 12th – Cap d’Antibes, France

1925 September 25th, 29th & October 13th – Cromwell Road, SW7 *

1925 Nov 18th – Alfred Place, SW7

1926 Jan 20th – Alfred Place, SW7

1926 April 13th – Mentone, France

Introduction to Correspondence

The correspondence covers a two-year period: 1924- 1926. This was a time when Muriel was living in Japan and struggling with her marriage. Silvia is constantly missing Muriel and wanting to see her again… and, no doubt, to see Hodgson too. Some of her intense and heart-felt sentiments are expressed in the following examples:

(I’m) Now sitting under the palm trees writing to my beloved Muriel

Darling Muriel write at once & tell me everything. My dearest love to you both. You can’t conceive how I long for you to be here. Your lonely Silvia

…I think of you both so constantly. It is a kind of twilight when you are away. I hate Victoria & Upper Gloucester Place because they remind me so of you. When we meet, the Turners, Rothensteins and me (all) say ‘If this or that had not happened, they wouldn’t have gone’ and then we say it again – futiley in different words. Siegfried Sassoon’s candles are not to be lit until you return. Oh, what a delicious day when your ship steams in.

…I dreamt last night that a letter came from you, so perhaps one will come soon, if I’m very good. We were all very worried at the time of the Earthquake*. I wonder how much you felt it. I think of you so constantly & have sort of tidal waves of loneliness – & other people seem inadequate.

Later I dreamt about you a second time – that you were coming home. I miss you more & more – in a kind of horrible crescendo. Sometimes for days on end you are never out of my mind. I wish I knew if you were well, both of you. I wonder if the earthquake affected the mails.

* Japanese earthquake on 23rd May 1925

Themes

Silvia jumps from one subject to another, so it is easier to summarise letters according to themes as follows:

1 Books & Plays

2 Zoo Portraits

3 Cote d’Azur

Originally, a ‘local gossip’ theme was intended but, as most of the extracts can be better added to individual webpages under the Friends’ Menu, it has been removed.

1. Books & Plays

As a former actress, Silvia retains her interest and in the theatre throughout her life, as well as in reading contemporary novels and poetry. In all but one of the letters she sends to Muriel, brief references are made – sometimes accompanied by ‘faint praise’- to the latest book she has picked up or a play she has heard about.

She read a book of literary criticism by (John) Middleton Murry and suggests that from a purely lay point of view, he does manage to make it all deadly dull. (Murry was partnered and eventually married to Katherine Mansfield; after she was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1918, Mansfield stayed [or lived?] in Mentone at one of the fashionable spas). In a letter, written from Mentone in 1925, Silvia writes that Aldous Huxley makes an Aunt Sally of Katharine Mansfield in ‘Barren Leaves’ and inserts chunks of her diary.

In November 1925, she posts (to Japan) a copy of a new book of poems which she thinks the Hodgsons will like, by W H Davies (= Later Days, the 1925 sequel to The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp). Later, in a one-liner, Silvia mentions that Naomi Royde-Smith has produced a successful & not very distinguished novel. She admits to never having read Dickens and considers that A Lost Lady by Willa Cather (publ 1923) is amazingly good.

The only play to which she refers is by Elizabeth Fagan. It is a comedy produced (probably by a brother, J B Fagan) at a charity matinee which Silvia heard went very well.

2. Zoo Portraits

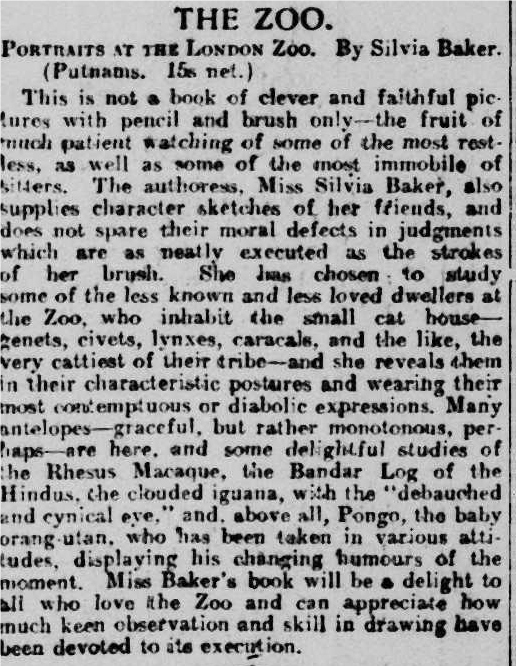

Silvia writes long, chatty letters to Darling Muriel whilst she was busy with the publication of Portraits in the London Zoo. This book was published in November 1925, albeit delayed by the Binders & Distributors who, to Silvia’s dismay, were on strike! Most of the letters provide an insight into Silvia’s experience of drawing animals at London Zoo.

She tells Muriel that she has been going to the zoo, when I ought to have been sorting and arranging drawings and launches straight into describing a collection of 5 orangs (which) arrived from Singapore – one, a baby of eighteen months, filled me with bliss, & I’ve been drawing him every day, inside a cage in the Sanatorium. He holds my hand for minutes at a time, and is the first animal that has ever been fond of me. He & 2 others were each in cages, within the large cage in which a gibbon was loose. He used to bag my razor-blades, and put them in his mouth, & steal my drawing-paper & eat it, & grab at my pencil, & pull my hair, & put his arms round my neck & it was very hard to concentrate.

She spends most of her time in the Sanatorium because it is so quiet & the animals sit so still. On one occasion she found a newly born fruit-bat there. It was blind & naked & most delicately shaped. Flesh-coloured, & with the expression of a sleeping chid – very queer (sic) indeed. She goes on to say that there is a marvellous collection of tropical birds being housed in the sanatorium just now. The Council (Lord Grey & the Duke & Chalmers Mitchell etc) roll up and gaze & value them & I hear from the next room snatches of conversation:

Magnificent bird of paradise – young male £80; female £60 & so on.

The sanatorium keeper is a friend and offers Silvia bananas from the monkeys’ rations. She writes that she is mad about monkeys but I have only learnt their heads & feet so far. She also drew a chimpanzee a little time ago – a baby. It came over in an aeroplane, caught a cold, & after a week or two it died. I drew it up to the last. It was heart-breaking – it wouldn’t eat – although the zoo people did everything they could.

Another colleague is the sign-writer who sits in the room next door (and) puts on gramophone records to please me. He used to be a stoker in the Navy, & is crammed with wittiness & friendliness. We discuss all the Admirals we know. Occasionally he offers criticisms of the way I hold my brush – I try to draw with the brushes RH gave me. He gives me inks too, & various papers to work on.

She enjoys sitting in the zoo library with wet towels round her head, surrounded by colossal tomes! This is because she is trying to compose descriptions of the animals she has drawn, giving details of their provenance, their size and colour and then adding a note about how she thinks they work as models or personalities.

The letters also describe the process of getting the Zoo Portraits published. Silvia had offers from Kegan Paul and Putnam’s and accepted the latter as it was a better offer. There was a deadline of 1st July 1925 and she had to work hard to get her drawings and notes ready in time.

She often met Putnam’s English director, Constant Huntington, at dinner parties and described him as perfectly charming. He was born in Boston, USA and died aged 86 in 1962. He married Gladys Parrish, an American author, in 1916. Not long after, they moved to London to open the English office for Putnam’s.

Huntington spent several months experimenting with various methods to colour Silvia’s drawing blocks. She writes that he then submitted the results to me in the most diffident way – saying “I’m terribly afraid you won’t like this… or that.” It makes me feel so grand, & important. I always go to his office expecting to be bullied, & find instead that he expects me to bully him.

Following the publication of Portraits in the London Zoo, she writes that she received lots of good notices. They included:

Praise on the wireless from Desmond McCarthy (the BBC only began operating at the end of 1922)

Lovely notice in the Burlington*

Half column & reproduction in Morning Post

Whole column & reproductions in Chronicle

A good notice in the Spectator

Notices in the Telegraph,* My photography, The Queen & Cassells Weekly

& others as well

Also a letter to my publisher from Sir Arthur Thomson (zoologist)

& a letter from my publisher to me saying “Everyone that counts is enchanted with your book”

Subsequently, we learn that Macmillan’s wrote from New York, murmuring something about publishing my book in America, but I don’t suppose it will materialise because of expense – and it didn’t materialise.

* From the Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 48, No. 274 (Jan., 1926)

PORTRAITS IN THE LONDON ZOO. It continues to surprise one that the “detached artist ” in England remains aloof from the art of illustration. No first-rate English artist of the younger generation has, for instance, tried systematically to describe London streets or buildings or parks. The Zoo is largely in the hands of the professional postcard man, who makes a dreadful mess of his material. Miss Silvia Baker has now, however, supplied us with a large number of drawings of the animals in Regent’s Park. They are distinctly in the French style; they are not photographic, nor are they designed, but occupy a chic niche between those two tremendous tendencies. Miss Baker’s powers of observation are of the best, and her technical mannerisms fit in very well with her turn for descriptiveness. The text of the book is scientific, but discursiveness creeps into it agreeably enough. It will be an acceptable book for the young dilettante who is willing to imbibe science in reasonable quantities.

*From the Daily Telegraph – 1st January 1926

Ralph Hodgson (RH) Subtext

Muriel clearly became one of Silvia’s special friends but I imagine that some of the anxieties and feelings which she expressed, are for RH to hear – via Muriel. In turn, they convey the extent to which Silvia is both beholden to, and fearful of, RH’s opinion. She wanted RH’s help terribly badly, but it seemed hopeless to ask him questions and wait 10 weeks for the answers. He will hate the book I expect & hurl it to the other end of the room, so I am collecting a portfolio of drawings for him, that he may hate less.

In two separate letters, she is at pains not to ‘disgust’ him and in a third writes: It is horrible that RH is disgusted with me. It’s no use attempting to justify myself – on an income of £75 a year one can’t publish books at a loss. My studio was overflowing with drawings & publishing somehow or other was a necessity…

Silvia asks if she can dedicate the book to RH and needs to know by the copy date. In spite of the negative vibes, he must have agreed as the dedication is in his name. Meanwhile, she struggles to use some brushes that he gave her – thinking I have conquered the technique & then finding that I haven’t…

3. Cote d’Azure

(NB Mentone is spelt in French being the way it is spelt in the letters)

Silvia mentions that her Godmother has a villa in Mentone but no name is given; presumably, this would have been a close friend to her mother. She later explains that she has travelled out to Mentone because her mother is very ill with influenza and ought not to be left alone. It makes her feel rather wretched about everything (such as what will happen next winter) and wonders what on earth shall I draw if I have to live in Mentone? But she enjoys swimming describing it as a solitudinous affair, for I have the whole Mediterranean to myself…

(Swimming in the sea was not a popular activity in the early part of the 20thC)

Silvia asks Muriel if she remembers the loggia around the Church of Miracles at Laghet, as well as the Mentone Donkeys that go up to St Agnès and the donkey women with their Chinesy hats. This suggests that either Muriel or Ralph, or both of them, stayed in Mentone prior to 1924 when they set off for Japan.

In the letter from Cap d’Antibes (extract below) the joys of staying on the Cap mingle with lots of local gossip, French style!

(Names which are underlined all feature on Wikipedia)

I am at Antibes now… I’ve never loved any place so much. It is paradise. You oil yourself all over, then sunbathe on a marble roof, then dive into 50 feet of crystal water, swim to a raft & sit there half the day talking to enchanting people.

Margaret Morris is here & her summer school, & Ferguson the painter, & large slabs of Chelsea & Hampstead & America. Lloyd Osbourne has a villa next to the Davison’s villa where we go to bathe. Lloyd Osbourne looks enchanting paddling about in a canvas canoe, dressed in white duck shorts & a blue linen coat, & a large straw hat (the kind horses wear) on the back of his head. Under the hat you see straggly white hair, enormous horn spectacles & a benevolent Uncle Sam kind of face. He & Floyd Dell & a young man called Maschwitz are to discuss the Future of the Novel at the Davison’s house.

The Davison ménage is very odd. He is a millionaire & director of the Kodak company. He is a Pacifist, a Free Love Addict, an anarchist & a Communist, & looks as if he couldn’t say Boo to a goose. Mrs Davison (there was no binding contract) is a Suburban little creature, but she loves children, & they have adopted nine. The villa is enormous, was built for the late King of the Belgians, & is called the Château des Enfants. Margaret Morris & her summer school & Ferguson, the painter, who teaches drawing to the school (he was a pupil of Manet) all stay at the Château.

I am doing some of her exercises every morning, so I am included in the school more or less. I had always thought her & her activities second-rate, but now I know more about them I am rather impressed. She is a great friend of Og’s, who made me come here & with whom I have all my meals. She has a school for dancing & trains children from about 12 to 20. They learn dancing & painting & French & that’s about all. They are the most enchanting creatures – full of imagination & vitality & simplicity. I’m awfully bored by young girls as a rule but not these. They simply pant for the next lesson. The only rule in the school is that girls under 21 must go to bed at 9.30 – otherwise they would be designing & making dresses & scenery & rehearsing & so on until midnight. They learn partly by teaching each other, which I think is a good way. I learnt such a lot about acting myself when I was teaching it.

Og* is very difficult to understand. You remember I told you about him. He has been a sort of fairy godmother to me. I think like all intellectuals he is slightly inhuman. He has a very high opinion of Carnaby (Prints) which endears him to me, but he is so sweeping in his condemnations, which freezes me. He dismisses Dickens with a wave of the hand, & that I think is a key to him. (Not that I’ve ever read Dickens myself, but one doesn’t brag about such deficiencies). Og lives in a state of simmering annoyance with me because I will converse with bores. He will only cope with distinguished & vital persons like Goossey, & Evan Morgan & Mrs Leyel and so on.

There is a Scotchman here who was Reuter’s correspondent in Paris during the Peace Conference. He certainly is a boring person but he loves Enid & Roderick** so of course we talk. I tell Og in excuse, that I like to see the world through a Scotchman’s spectacles & he says that all Scotchmen have the same sort of reactions & one ought to have got to know them by the time one was 7 – moreover you don’t get wine out of thistles. Hilda Leyel says Og has no soul. It is a vague sort of remark, but there’s something in it. He is so benevolent, & can be so interesting to listen to – I wish I could come to a definite opinion about him.

There is a thunderstorm going on – very tropical. It rather alarms me. There was one this morning. I bathed in it. The rain came down like swords – getting closer & closer together, till they beat down your eyelashes and you couldn’t see your way.

Additional Correspondence

The second group of letters reinforce some of the observations already noted in the analysed Themes above. For instance, she waxes lyrical about the Côte d’Azure:

Antibes was marvellous beyond all telling. The tropical nights were so lovely. One came under a spell. Everyone did. After midnight time ceased entirely – people changed – there were no appointments to keep, no grind, there was no reality.

But on return to London ‘the first germ (she) met at Victoria Station’ bowled her over and gave her a violent cold!

Disconcertingly, Silvia who regularly lived on a shoestring, admits to pawning all her necklaces and living on £10 borrowed from Uncle Charles (Sept 1924).

We learn about Dr George Vevers who was the Superintendent at the Zoo in Regent’s Park from 1923 – 1930. He then moved to oversee preparations for the opening of Whipsnade Zoo, also run by the Zoological Society of London. Silvia describes him as a one-time bien-aimé; they seem to have had an uneasy relationship which is referred to as ‘Vevers nonsense’ (April 1925).

Likewise, we learn more about Ogden* who appears to have had a crush on Silvia. She describes him as a ‘highly intelligent and friendly person’. She recognises that, with RH’s removal, it is a ‘kind of providence’ to have been befriended by Og, even if ‘margarine is not butter’! He talks ‘metaphysics for hours on end – till 2 in the morning’; on at least one occasion, in the all-night Lyons Corner House. She writes that ‘although he has fair hair & thick glass spectacles (like the aquarium tanks) he is a strong silent man and I am cheese in his hands – cream cheese.’

*Charles Kay Ogden was known as Ogden, Og or CK. He is described as an Editor & Polymath. He advocated the use of an international Basic English, consisting of 850 words that are needed for everyday use. He became an advisory editor to the publisher Kegan Paul in the early 1920s. http://ogden.basic-english.org/memoirb3.html

**Enid (née Bagnold) & Roderick Jones

– For Love of a Rose by Antonia Ridge (1965) tells the story of the Peace Rose; part of it is based on Cap d’Antibes and shows how unspoilt the area was in the early 20thC.