Silvia’s friendship developed with Norman Pearson & Colin Fenton because both Pearson & Fenton had a special interest in poetry and both intended to write a biography about Ralph Hodgson (RH). Neither succeeded in the latter – partly because their own lives were too busy and partly because Hodgson was notoriously reticent about his life story. In the process, however, they were each introduced to Silvia, thanks to her long-standing friendship with Hodgson. After Silvia died, a third person comes into play, an academic called Mary Lago who questioned the destination of Silvia’s letters.

PROFESSOR NORMAN HOLMES PEARSON (1909-1975)

Pearson was an ardent follower of Hodgson’s poetry. He was born on 13th April 1909, in Massachusetts, where he was brought up and educated. Following an unfortunate fall as a child, his hip was badly affected. He endured a series of operations and spent much of his youth in a wheelchair. During the 1930s, he studied English at Yale College and Oxford University. In due course, this led to him becoming Professor of English & American Studies at Yale University. His research focussed on Nathaniel Hawthorne (novelist) and Ezra Pound (poet). He was a prolific writer and edited several poetry anthologies. He also managed the literary estates of HD (Hilda Doolittle, who at one time was engaged to Ezra Pound) & her companion, Bryher.

In 1943, during WW2, Pearson was recruited to the counter-intelligence section of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in the UK. It provided a link between the OSS & Bletchley Park. His office was off St James Street in London and HD’s daughter, Perdita, worked there as well. It was above the MI6 office run by Graham Greene with whom Pearson would have regular conversations; according to Greene, these always began with literature.

After the war, through his network of literary and artistic contacts, Pearson set up an American Studies programme at Yale and helped to build up the Yale Collection of American Literature. It included a variety of formats ranging from correspondence to artwork, to essays and several other miscellaneous archives in between.

One of Pearson’s American contacts – George Plank, aka Plankino – suggested that he acquire Silvia’s letters. Correspondence ensued and, by March 1963, Plankino was pleased to learn that Silvia had agreed to this request. At the end of March, the Professor and his wife, Susan, visited Silvia and she tells the Hodgsons that she liked them very much. The three of them subsequently met in London on a number of occasions and the Pearsons bought one of Silvia’s watercolours. On a visit to Amsterdam in 1968, they sent her a card of a Rembrandt lion which reminded them of her lion drawings – how could we think of you otherwise…

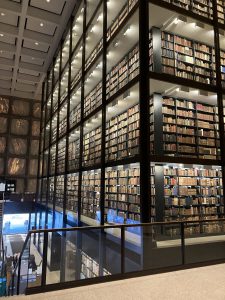

At some point, Pearson asked her to write a memoir of RH. To achieve this, however, she needed copies of the letters she had bequeathed to Yale. This meant that photocopies were mailed back to the UK and by June 1963, Silvia wrote that she was very happy to have them. The family has her original hand- written memoir (more often referred to as an Essay) and a copy is held in the Beinecke Library. It is a bit of a ramble but was written when Silvia was in her 70s and beginning to suffer from dementia.

COLIN FENTON (c.1929-1982)

Throughout his life, Colin Fenton loved literature, particularly poetry and, like Pearson, he was a devotee of Hodgson’s poems. Silvia was introduced to him, in 1957, by Shirley Colquhoun (the daughter of Vere Chatteris, Ralph Hodgson’s sister-in-law by his first marriage).

Fenton read History at Oxford and went on to work at Harvey’s of Bristol. In 1960 he became a Master of Wine and, ten years later, was invited to become the first head of Sotheby’s newly formed wine department. He travelled widely and visited the Hodgsons in Ohio as well as Pearson at Yale. He married in 1973 but died in 1982 at the age of 53.

Silvia describes Fenton, variously, as a beautiful young man with dazzling charm and such lovely manners. She was impressed with his knowledge about pictures and the fact that he sees through the intellectual nonsense of much modern criticism in journalism. In 1959-60 she drew a picture of him for the Hodgsons. He was difficult to draw but she gave him one of her Tahitian drawings as a prize for sitting so still! The Hodgsons were delighted and thanked her for a lovely drawing with extraordinary power.

In his letters to Silvia, Fenton wrote more than once that he was still trying to assemble his notes together in order to write a memoir about Hodgson. Meanwhile, in 1958, he sought permission from RH to edit his unpublished works. The result was a limited edition of The Skylark, illustrated by Reynolds Stone. The publisher was the Curwen Press and they printed 350 copies. The first 50 were bound in black morocco leather and signed by both Hodgson & Stone; the remainder were bound in buckram and signed by Stone. It proved a great success and brought Hodgson back into the limelight. The following year, it was re-issued by Macmillan and then, in time for his 90th birthday in 1961, Macmillan published RH’s Collected Poems, also edited by Fenton.

Hodgson’s health had deteriorated for several years and, as he approached the age of 90, he was nearly blind and bed-ridden. It must have been a relief for everyone to learn that, in November 1962, he died peacefully in hospital. Fenton wrote to Silvia to confirm his death, adding that he loved you dearly; I heard that in his voice when he exclaimed ‘Good old Silvia’ looking at your pastel drawing. Also, he knew you had genius.

Evidently around 1967, Colin asked Silvia if he could borrow the xerox copies of her correspondence with Hodgson. These were duly forwarded to him. However, on their return, Silvia thought some of them had gone missing – maybe such thinking was caused by her memory loss. She contacted Pearson for a checklist and, in February 1968, he belatedly wrote to reassure her that they were all present and correct. He had, however, had difficulty in finding her papers until he realised that he had filed her earlier letters under ‘Baker’ and her later ones under ‘Hay’. As an aside, he added that following a recent wedding anniversary dinner party, he and Susan wished Silvia could have joined them – along with her paint brush!

MARY LAGO (1919-2001)

In 1971, there was an academic ‘spat’ between Professor Pearson and Mary Lago. Lago was an author and English Lecturer at the University of Missouri. In 1968, she was granted permission by John Rothenstein to obtain material, written by his parents, from various libraries and collections. She edited William Rothenstein’s correspondence that he had with both Rabindranath Tagore and Max Beerbohm. Subsequently, her abridged version of Rothenstein’s three volumes of Men & Memories (including Since Fifty) was published in 1978.

Following her death, Silvia’s (sole) executor made contact with Lago, probably about the correspondence between Rothenstein and Silvia. This caused some confusion which is reflected in copies of the following three letters.

The first indicates that Lago and other academics couldn’t work out how Norman Pearson had acquired so many of Silvia’s letters, especially those from William Rothenstein. Lago suggests that the Professor was prone to hoarding artefacts that were not always his to possess.

In the second letter, Lago informs the executor that she had written to Pearson requesting photo-copies of all the letters which he had obtained from Silvia. Lago sounds indignant that Pearson may not have paid for the manuscripts and insists that they should have been made available to scholars.

The third letter is sent from Pearson to Lago in which he explains how he came to know Silvia (through Plankino). From this letter it transpires that, in the late 60s – as her health declined – she asked Pearson if he would be willing to pay for the letters which she had sent him. Pearson did so, having consulted dealers about a ‘fair price’. At this point, Silvia may have moved to her nursing home. Pearson didn’t hear from her again and wasn’t aware that she had died until Lago wrote to him. He finishes by saying Silvia was indeed a charming person and both my wife and I were very fond of her.

In the end, Pearson died in 1975, just 5 years after Silvia. He bequeathed his extensive collection, including Silvia’s material, to the Beinecke Library where it has since been available for research purposes. As a family, we are grateful that Silvia’s letters were saved for posterity – had they been discarded, we would have known little about her varied life and missed out on the details of her wide-ranging travels which came to light through her letters, as well as those of her many friendships.

SOURCES:

https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/article/norman-holmes-pearson-papers

https://www.fentonartstrust.org.uk/the-foundation-of-the-trust-and-its-benefactors/

https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/collections/show/36

Silvia Baker Papers: General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Dreaming of Babylon, The Life & Times of Ralph Hodgson by John Harding: (2008) Greenwich Exchange, London

Graham Greene: ‘Room 51’ in The Sunday Times, p10 (14.07.63)