There are two notable occasions which lend support to the fact that Clough Williams-Ellis and Silvia knew each other well. The first is her wedding, as he escorted her up the aisle. The second is a warm introduction which he wrote for her first travel journal: Alone and Loitering.

Having read Clough’s Autobiography I realise that Silvia would have also known his wife, Amabel, who was just a couple of years older. Amabel’s father was editor, as well as proprietor, of The Spectator and a first cousin of Lytton Strachey. Her brother, John Strachey, was a journalist and MP who, after WW2, became a Minister in Attlee’s Government.

Amabel married Clough in 1915, in a small chapel, close to her home near Guildford. She worked for The Spectator, variously, as the poetry critic, drama critic and then literary editor. She published An Anatomy of Poetry and had links with the Georgian Poets – as did Silvia’s ‘mentor’, Ralph Hodgson. Alongside this connection, Clough was a friend and admirer of Claud Lovat Fraser’s designs and use of colour. In 1913, Lovat established a small publishing firm along with Hodgson (& Holbrook Jackson). It seems reasonable, therefore, to assume that many of the literary and artistic friends of the Williams-Ellis’s, overlapped with Silvia’s.

Clough was a flamboyant and unconventional character from a staunch Welsh background. He appears to have been obsessed with buildings and architecture from an early age and went on to become an influential architect, conservationist and town planner. Clough was invited to design numerous houses for the upper echelons of society – most of whom would have been Tory voters – whereas he grew up in a Liberal environment and later became a Labour supporter. At some point he was the President of the Design and Industries Association (DIA) and he was actively involved in the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE) which was founded in 1926.

Following WW2, Clough was instrumental in establishing the Snowdonia National Park (1951). This was third national park of its kind and the first in Wales. Its boundary included the estate which belonged to the Williams-Ellis family and the Portmeirion peninsula.

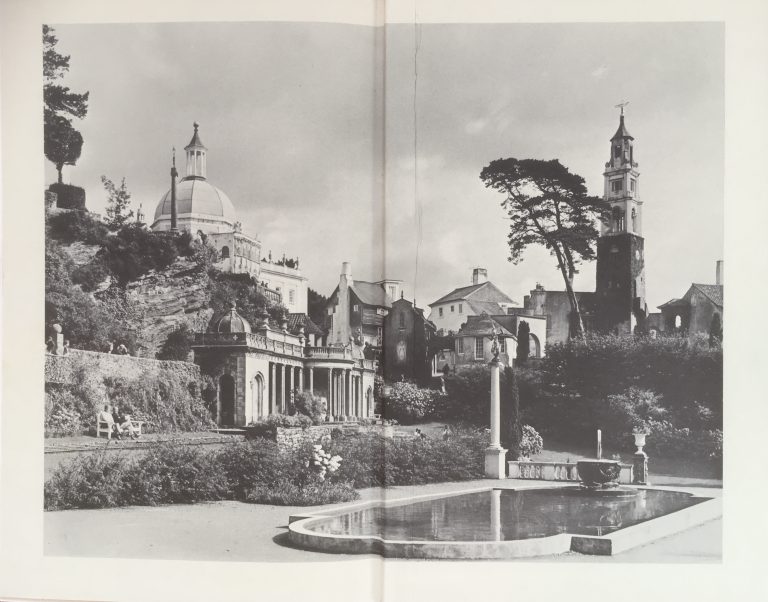

The creation of the Italianate village of Portmeirion is, perhaps, Clough’s most memorable legacy; it is now run by a charitable trust. In his autobiography, he describes the opening of the Portmeirion hotel. It took place over the weekend of Easter 1926 (13th April). He admits that ‘everything was pretty rough, primitive and slapdash; the staff untrained, the management unsuitable and the food terrible’! In spite of its shortcomings, a group of friends were ‘suddenly thought up’ and invited to stay. The party included: ‘a prominent political peeress suitably squired by an ex-minister, a dramatic critic and a couple of actresses, a psychiatrist, an editor, a woman magistrate, two novelists and I suppose about a score of others equally various’.*

It transpires that Silvia must have been one of those guests! This became apparent from a letter she wrote, in April 1926, to Muriel Hodgson about a glorious week with the Williams-Ellises in N. Wales – near Port Madoc, where Shelley stayed. She goes on to describe a couple of events:

First: We bathed – it was bitterly cold – & I was in a sailing dinghy that overturned. I swam for dear life with all my clothes on & then discovered to my rage & fury that I was in my depth. A young man on the bank was grinning like a Cheshire Cat. Then I was sent to have a hot bath, & they said they’d send me dry clothes, so I sat for about an hour in the hot bath & they forgot me, & I had to drape a cork bath mat lovingly round me & scream for the butler.

Secondly: There were crowds of very nice people there – Dorothy Massingham for one – & there was something in the air that made everyone like everyone else – & there were lovely toys – motor cars & 3 1/2 ton yachts to play with. There was a woman of about 70 called Lady Sheffield. She looked 50, & had led a marvellous life of discreet Edwardian gallantry. Her adorer of the moment (in tow) was a dignified, deaf solid ex Liberal Cabinet minister.

The second event ties in with Clough’s description above, conveniently letting us know who the prominent peeress was! Dorothy Massingham was an actress – brother of H J Massingham (author & poet).

Twenty years later, ‘on the edge of our first post-war winter’ Clough prepared some comments which were used as an introduction to Silvia’s book about her travels during WW2.

He says that he was allergic to the manuscripts of other writers but, on this occasion, he read every line of Silvia’s ‘uncorrected typescript’. In a somewhat convoluted way, he is very complimentary about both her drawings and descriptions but suggests ‘the whole book has a secondary and subtle charm in the way that one seems to catch a reflection of the Author’s own character – now clear, now wavering or amusingly distorted…’ He describes himself as an ‘old friend’ and tells us that he bought one of her ‘giraffe studies’.

Unfortunately, we do not have any correspondence from Clough and any letters that Silvia may have written to him would have been lost when his home (Plâs Brondanw) burnt down in 1951. All his papers were destroyed – presumably, including the giraffe sketch as well.

*Architect Errant: The autobiography of Clough Williams-Ellis (1971): London, Constable – p107